Carter's Hunting Red

Carter's Ink (Boston, Mass.) changed their cubed bottle design to the 'new oval' in the early 1940s, giving their product line a new facelift. The ink looks and performs very similarly to their Permanent Red and Sunset Red from the early to late 1930s. Some have considered this color red similar to venous hemoglobin (human blood). There are definitely some brown undertones. I think it's more brick-red.

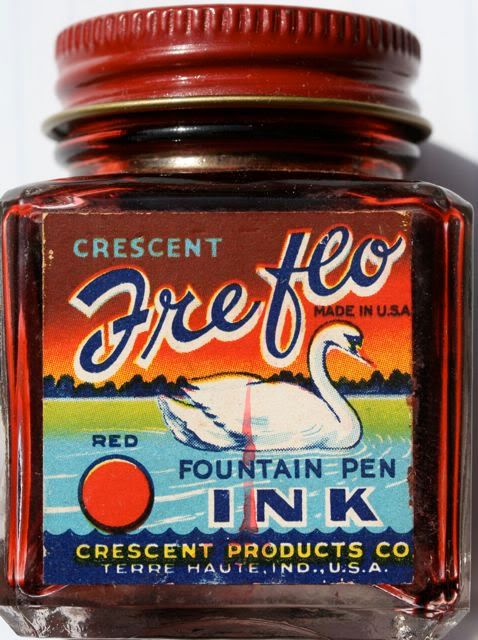

Crescent Fre-Flo Red

A carmine red produced by Crescent Products Co. (Terre Haute, Ind.). See review here.

Sanford Pen-It Cardinal Red

Sanford (Chicago, Ill.) began producing their Pen-It ink in cute little jars, probably around 1937, up until the mid 1950s. These 1-ounce bottles were initially presented in commemorative catalin (plastic) globes for the 1938 New York World's Fair. The ink is very similar to Pelikan Brilliant Red (or Noodler's Dragon's Napalm, modern), with pinkish-orange undertones.

Pelikan Brilliant Red

Wilhelm Wagenfeld created one of the classic ink-bottle designs in 1938 for Günther Wagner Company, makers of Pelikan pens and inks. This bottle was produced by Vereinigte-Lausitzer-Glaswerke VLG Weisswasser. Pelikan red ink still produced today. It is a translucent red analine dye with orange and pinkish undertones, very similar to Sanford's red ink seen above.

Carter's Sunset Red

Carter's cube shaped bottles of the 1930s are a favorite among collectors. Initially, Carter's released the 'Sunset' series of inks, with all of their brightly colored inks, even green, labeled with the 'Sunset' moniker. I presume that while there may had been many changes to their formulation, the red color has remained consistent, no matter how many different ways it has been renamed and repackaged.

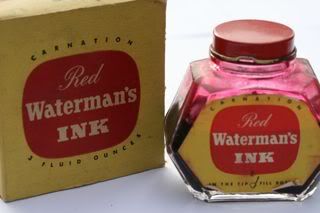

Waterman's Carnation Red

Although Louis Waterman’s company is noted for the capillary feed and the cartridge-filling mechanism (thanks to its French subsidiary JIF-Waterman), one of its most well-recognized company designs comes from someone outside of Waterman; that is, the Waterman ink bottle. Ted Piazzoli was an employee of Capstan Glass of Connelsville, Pennsylvania. As such, he designed several patented jars and bottles that he signed over the rights to the Capstan company, all but the one Waterman ink bottle. He was granted the rights to this patent in March 1936. Capstan produced the first jars for Waterman. In 1938, Capstan was reorganized as Anchor Hocking. In the early 1950s, Waterman released its larger 3-ounce ink bottle. Carnation red has a nice rose-pink shading, similar in look to Sheaffer's Skrip Persian Rose.

Sheaffer Skrip Red

Sheaffer Skrip Persian Rose

Here are two classic Sheaffer inks from the 1950s. Since the 1940s, Sheaffer began producing a glass bottle with a small well at the top for users to dip their fountain pen nib without dipping it straight into the mother lode. Skrip Red is considered by many to be a "true red," whatever that means. I think it's shade represents the color of a stop sign. Perhaps you're not seeing stop-sign red in my photographic sample. However, when you brush the ink onto the page, it becomes very clear. Skrip's Persian Rose is what I call the mythical ink for two reasons: one, it's a color that has been copied by several ink producers over the past 70 years; two, because of instability of the dye, no two Persian Rose inks remain exactly the same. Some have a nice deep rose color like you see here, others have turned to an avocado green. You can still purchase Skrip Red ink new. But Persian Rose is a rare find, with bottle prices ranging from $25 to $85 for a 2-ounce bottle.

Parker Quink Red

I love these diamond-shaped bottles from the late 1950s-early 1960s. Parker's Quink ink was originally formulated in the 1930s. Quink red has a very pleasant cherry-red color that calls attention to itself when using it for marking up black typed copy. It's a bit bright as a regular writer on a filled page.