Here is an example my penchant for taking a very innocuous subject and producing a marathon of information.

The #dailyarsenal or daily arsenal of writing instruments

was a hash tag on Twitter started by, I think, @DIYSara. It caught on quickly,

as various folks will still post pictures of the pens, inks and papers that

they are using that very day. Usually, on my blog, I try to post some relevant and

useful information, if only to a very small audience. This one breaks that

tradition. This post is completely useless except to reveal my odd relationship

with writing instruments.

As an extension of some mild form of compulsive disorder, I

have always had a fascination with writing instruments. When I was in school, I

had The Lucky Pencil: This was the pencil that I took with me during tests. The

Lucky Pencil evolved into a mechanical pencil, which went with me everywhere. I

think it was a Parker mechanical pencil, steel top over a blue section. One

does not lose The Lucky Pencil, because that would be very unlucky. Eventually

after several years of use, The Lucky Pencil broke, or was lost, or whatever.

Maybe it’s around here somewhere in the house. Maybe its stored in some aluminum

air-tight special container.

The Lucky Pencil eventually evolved into The Lucky Pen. The

original pen was a Retro 51 Tornado roller-ball. It was aluminum pen with a

copper anodized finish. I must have gone through $3 or $4 weekly in roller-ball

refills for this pen. I used to

find gel-ink refills from cheap plastic pens, and modify them for use inside

the Retro 51. That pen was with me for nearly 6 or 7 years, until I eventually

lost it. It was so beat up after years of use, that I was more bothered by the

idea of losing the pen than actually losing it. I tried to replace the pen, but

it wasn’t the same.

I purchased a fountain pen because I grew tired of buying

gel-ink refills. I thought, if I can purchase just one fountain pen and one

bottle of ink, I would be set for life. My first ‘real’ pen was a Pelikan M215,

probably the best purchase I ever made. However, I rarely use it any more. I

have bought and sold more pens over the last 4 years than I could ever imagine.

Why do I write with a fountain pen? I enjoy the application

of a nice even line of ink with barely touching the nib to the paper. It’s not

as easy as it sounds. Once you apply the point to the paper, it’s best to not

lift it off. I forced myself to

retrain my hand. It took several weeks to figure it out, but now I don’t want

to ever go back. I can’t stand

writing with ballpoint pens, unless I’m writing on thermal paper. But I’ll save

that for another blog post.

So, after handling hundreds of pens, I have honed down my

choices to one or two pens out of perhaps ten that I carry as part of my

regular starting rotation of writing instruments. Some of my favorite writers

are Parker 61s, Parker 51s, Parker 21s, a flattop Sheaffer, the TWSBI pen, the

Eversharp Skyline, Waterman Emblem (100-Year) and a Moore 94-A. Once I have locked pen and ink into

regular rotation, I rarely let it go.

I have a medium-point Parker ’61’ (shown here) with stainless steel cap

and red body (circa 1958). I mixed up a concoction of my version of rose-colored ink

(copying the Skrip Persian Rose color of the 1950s) using Rohrer & Klingner

Solferino and Fermanbuk (purple and red).

The red ink went well with the red pen. I love this pen because it

doesn’t skip. It doesn’t blort out ink. The ink always stays true to the feed.

Plus, you can carry it on planes without the pen leaking.

My other go-to pen is a Parker ‘51’ demi-sized (shown here) that someone

gave to me (circa 1947). It has a razor sharp extra-fine point, but always writes smoothly.

I initially loaded Private Reserve’s Tanzanite (violet blue), and have

practically gone through half-a-bottle before I decided to clean out the pen. I

have since switched to Noodler’s Dark Matter temporarily. The ‘51’ handles this

ink well. But I miss writing with Tanzanite, and plan to switch back.

With a couple of regular starters, I’ll mix in one of my

guest-pens off the bench. These are pens that I may have purchased recently or

in the past that have not gone into regular rotation. Maybe they have an odd

filling system, or like the Eversharp Skyline, require frequent refilling.

Maybe the flow from the feed is a bit odd. Perhaps it has a flexible nib.

Flexible nibs are more of a novelty. They are designed to be used without

bending the nib. But you can’t help adding a little shading or flourish to your

capital letters.

I have acquired a couple of old Charles H. Ingersoll

‘Dollar’ pens. My latest one has an uncommon fleur-de-lis pattern stamped into

the pen (shown here). In 1924, Charles Ingersoll of the "Dollar Watch" fame, formed the Charles Ingersoll Dollar Pen

Company in Newark, later moving to East Orange, New Jersey. Ingersoll's company wasn’t the

only company in history to produce a “dollar” pen (e.g. Evans or Esterbrook).

But clearly, Ingersoll was trying to capitalize on the Dollar Watch fame. The

company existed until about 1931, producing a nickel-plated brass pen with a 14

karat gold nib and iridium tip. These pens sold for $1.00. That’s $12.50 in today’s

economy. The company marketed their pens to compete against the low-end

nameless pens with steel nibs. Ingersoll offered high quality 14-karat gold

nibs with iridium tipping, much like the “$50” Waterman’s or Parker’s of the

day. Ingersoll however saved on manufacturing and material costs. Ingersoll

used brass tubing stock for the body and cap, cheaper, and more readily in

supply. It was also easier to form. They avoided cutting a slot into the side

of the pen for the lever. Instead a large upholstery tack was used as the

filler. It was a simple filling mechanism, but one that also drew up a large

amount of ink.

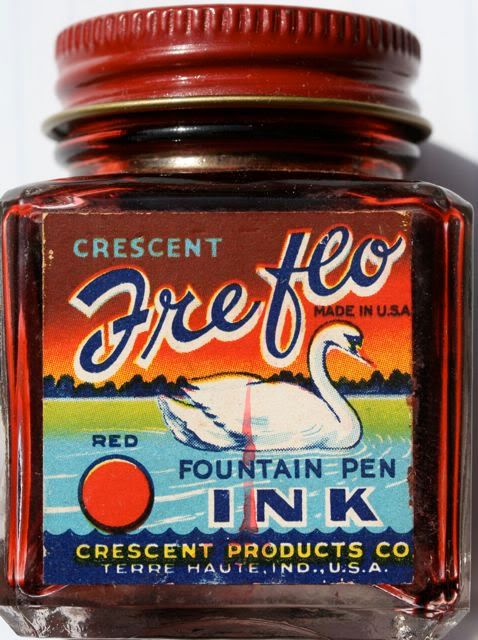

The ink used in the Ingersoll pen is another weird mixture, but also a bit of an

accident. I was trying to mix up another batch of my faux Skrip Persian Rose,

and used Rohrer & Klingner Scabiosa instead of Solferino. The result is a

dusky rose-red. It’s a pleasing red that’s easy on the eyes. However, the weight of the brass pen

quiets any enthusiasm for extended writing. Once this pen has dried its ink, it

will go back into the box and I’ll add another guest-pen into rotation.